Ethan Mollick on Humans Sounding Like ChatGPT

Exploring Ethan Mollick's viral claim that talks are adopting ChatGPT-favorite words, and what that means for communication.

Ethan Mollick recently shared something that caught my attention: "Everyone is starting to sound like AI, even in spoken language." He pointed to an analysis of 280,000 transcripts from talks and presentations that found speakers increasingly used words that are favorites of ChatGPT. Then he added the kicker: "Model collapse, except for humans?"

That short post is doing a lot of work. It is not just a fun observation about catchphrases. It suggests a feedback loop where AI-written text influences human writing, which influences human speech, which then becomes the data environment future models learn from. If that loop tightens, we might all converge on the same glossy, frictionless style.

In this post, I want to expand on Mollick's point in a practical way: what the research finding likely means, why it is happening now, and what you can do if you want your communication to sound more like you and less like the average of the internet.

What Mollick is reacting to

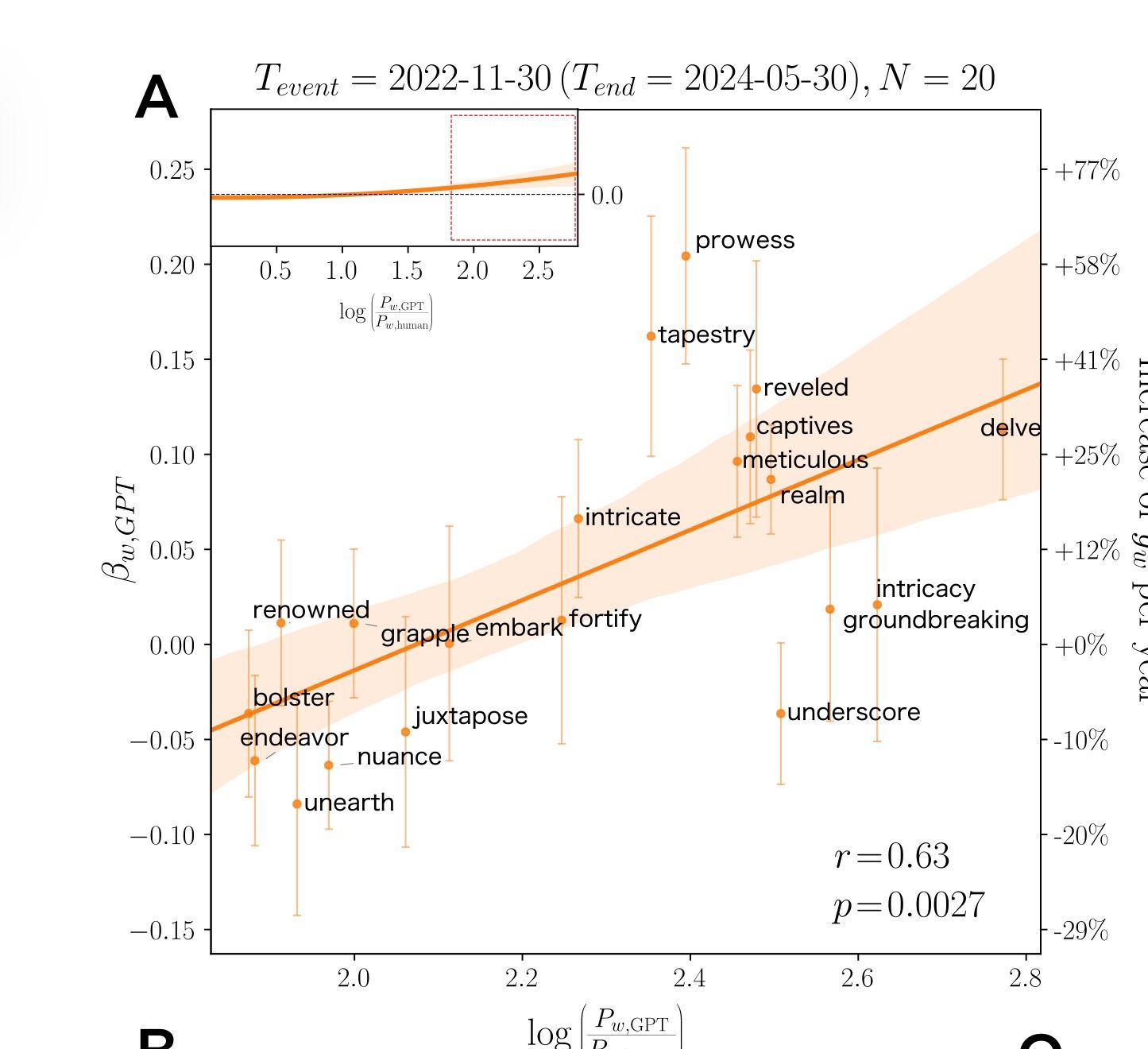

Mollick is referencing a paper that examined transcripts from academic channels and tracked the rising frequency of certain words and phrases associated with ChatGPT output. The core claim is not "people are using AI to write their talks" (though some are). The subtler claim is that even when people are speaking, their language is drifting toward the patterns we associate with AI-generated text.

Two details matter here:

- The dataset is large (280,000 transcripts), which makes trend detection more plausible.

- The domain is talks and presentations, which sit at the boundary between writing and speech. Speakers often prepare notes, rehearse, or read slides, and that preparation pipeline is exactly where AI tools can seep in.

Key insight: when a communication format is partially scripted, changes in writing style can quickly become changes in speaking style.

Why "ChatGPT-favorite" words spread so easily

When you read enough AI-generated prose, you start to notice a vibe: tidy structure, heavy signposting, and a preference for certain connective tissues. Think of words that telegraph clarity and completion: "delve," "explore," "crucial," "in today's world," "let's unpack," "key takeaway," "it's important to note." Not all of these are bad. The problem is volume and sameness.

There are at least three mechanisms that can make these words spread, even if no one is intentionally copying a bot.

1) The convenience loop (AI as default draft)

People use AI to draft:

- conference abstracts

- speaker notes

- slide headlines

- webinar scripts

- meeting summaries

Even if the final delivery is spoken, the source material often starts as text. If the text begins with AI, the spoken language inherits AI patterns. Over time, that becomes the new normal cadence for "professional" communication.

2) The optimization loop (platforms reward generic clarity)

On LinkedIn, YouTube, and corporate internal channels, content that is immediately legible tends to win. Clear hooks, numbered sections, tidy conclusions. AI is very good at that surface-level clarity, so creators who want to perform well may unconsciously adopt the same scaffolding.

This is a tricky dynamic: the more people optimize for what performs, the more the performing style becomes the culture.

3) The imitation loop (we mirror what sounds competent)

Language is contagious. If the speakers you admire use a certain cadence, you borrow it. If your colleagues start presenting with AI-polished transitions, you may follow to avoid sounding "messy" by comparison.

The result can be a flattening of voice: fewer idiosyncrasies, fewer weird metaphors, fewer sharp edges.

"Model collapse, except for humans?" What that could mean

Model collapse is the idea that if AI systems train on AI-generated data, errors and blandness can compound over generations, degrading quality and diversity.

Mollick's playful question asks whether humans might be doing something similar: if we increasingly consume AI-shaped language and then reproduce it, human communication could also converge.

I think it helps to split this into two risks:

Risk 1: Semantic collapse (saying less while sounding like more)

AI-leaning language can be high on fluency and low on specificity. It often uses:

- broad claims ("this is transformative")

- vague intensifiers ("incredibly," "truly")

- generic nouns ("solutions," "insights," "value")

You can deliver a talk that sounds polished while transferring less concrete information. If audiences get used to that style, they may stop demanding precision.

Risk 2: Social collapse (trust and originality)

When everyone sounds the same, it is harder to tell who has done the work. Audiences may start to discount polished phrasing as a signal of competence, the way we now discount stock photos as a signal of authenticity.

That could push communication toward two extremes:

- hyper-polished, templated, low-trust corporate speech

- raw, personal, messy, high-trust speech

If you care about credibility, you probably want the second style, but with enough structure that people can follow.

Why spoken language is especially vulnerable

It seems counterintuitive that speech would be affected. We usually think of speech as spontaneous. But modern speaking is often "written speech": slide decks, teleprompters, scripted intros, repeated keynote circuits.

Add remote work and recording:

- People rehearse more because talks are recorded and shareable.

- People rely on notes because they are multitasking on video.

- People want fewer stumbles because clips get cut into shorts.

All of that increases the incentive to pre-write, and pre-writing increases the likelihood of AI assistance.

A simple test: does your talk pass the "specificity filter"?

If you want to avoid drifting into the average AI voice, try this quick filter on a paragraph of your script or a section of your slides:

- Circle every abstract noun: "innovation," "impact," "strategy," "value."

- For each one, force a concrete replacement: a number, an example, a story, a named person, a constraint.

- Remove at least one intensifier: "very," "really," "incredibly," "deeply."

Here is what changes:

- "This approach delivers value" becomes "This reduced onboarding time from 3 weeks to 5 days."

- "We need to explore the implications" becomes "Here are the two decisions this forces next quarter."

Specificity is the antidote to generic fluency.

Practical ways to keep your voice human

I do not think the answer is "never use AI." The goal is to prevent unedited AI patterns from becoming your default register.

Use AI for structure, not sentences

Ask for an outline, counterarguments, or examples to investigate. Then write the actual sentences yourself. This preserves your cadence and your preferred level of certainty.

Keep one "rough" pass

Before polishing, record yourself explaining the idea to a friend for 60 seconds. Transcribe it. Use that transcript as the base. Your natural rhythm will show up in sentence length, word choice, and where you pause.

Replace signposting with stakes

AI loves signposting: "In this article, we'll cover..." Human talks often start with stakes: what is at risk, what changed, what surprised you.

Instead of: "Today I want to delve into three key trends."

Try: "Last year this worked. This year it failed, and it surprised me."

Add one non-obvious detail per minute

A rule of thumb I like: in a 4-minute segment, include at least four details that could not have been written without real context. A tool name, an edge case, a tradeoff you faced, a quote you heard, a number you measured.

That is hard for generic language to fake, and it is what audiences remember.

The bigger implication for creators and leaders

Mollick's observation lands because it connects AI to culture, not just productivity. If a large share of professional communication becomes AI-shaped, then:

- standing out will require more voice, not more polish

- organizations will need stronger norms around clarity and evidence

- audiences will become more sensitive to generic phrasing

In other words, the competitive advantage may shift from "can you produce content" to "can you produce specific, grounded communication that sounds like a real person who made real choices."

If everyone can sound fluent, fluency stops being impressive. Precision becomes the differentiator.

Final thought

I appreciate Mollick's framing because it invites curiosity instead of panic. "Everyone is starting to sound like AI" is both a warning and a prompt. If you notice the drift in yourself, you can correct it with small, practical habits: fewer templates, more concrete detail, and more of your actual spoken rhythm.

Attribution: This blog post expands on a viral LinkedIn post by Ethan Mollick, Associate Professor at The Wharton School. Author of Co-Intelligence. View the original LinkedIn post →