Adam Janes and the $10,000 Skill in the AI Era

A deeper look at Adam Janes's $10,000 invoice analogy and what it reveals about software development skills in the AI era.

Adam Janes recently posted something that made me stop scrolling: "I finally understand that old $10,000 engineering invoice joke." In his viral LinkedIn post, he tells the story of the giant machine that breaks down, the expert who taps one specific spot with a hammer, and the $10,000 invoice that follows.

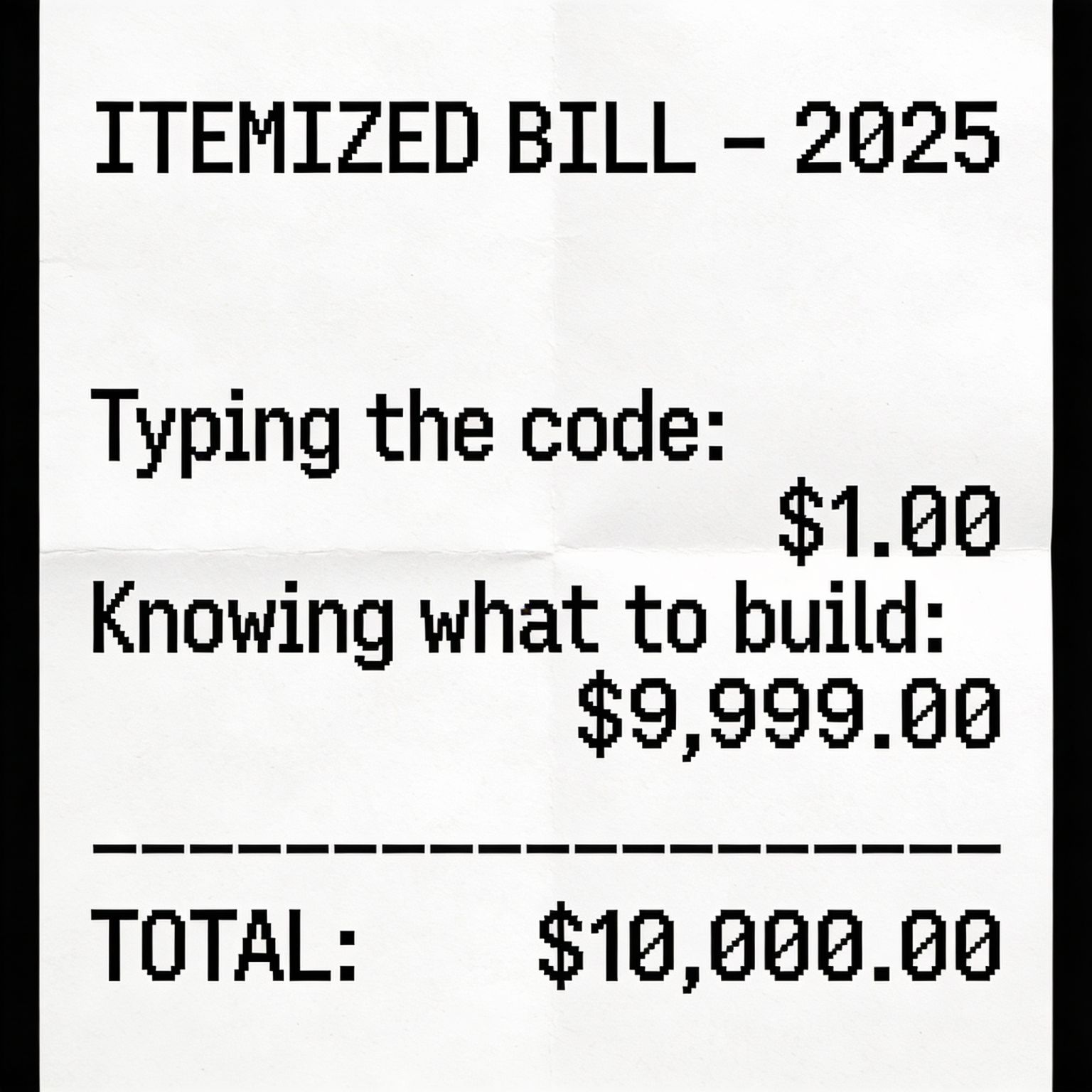

The breakdown of the invoice is famous:

- Tapping with hammer: $1

- Knowing where to tap: $9,999

Adam Janes uses this analogy to describe what is happening to software development right now. Tools like Cursor, along with modern AI coding assistants, have made the "tapping" part of the work nearly free. Generating syntax, churning out thousands of lines of code, filling in boilerplate — all of that is cheaper and faster than ever.

But the "knowing where to tap" part? As Adam Janes points out, that just became one of the most valuable skills on the planet.

From Typists to Directors

Adam Janes argues that we are moving from being typists to being directors. That simple phrase captures a profound shift.

For years, many developers were paid primarily for their ability to write correct code quickly. Your value came from being a fast, accurate "typist" of logic: translating requirements into syntax by hand. Today, AI tools can:

- Scaffold new projects in seconds

- Generate full functions or classes from a comment

- Suggest refactors and tests automatically

In other words, the typing itself — the mechanical act of writing code — is no longer the bottleneck.

"Tools like Cursor have made the tapping nearly free. The actual writing of syntax costs pennies."

If the typing is cheap, then where does the real value move?

To the people who can:

- Decide what to build

- Understand how systems should be designed

- Recognize whether what the AI produced is correct, secure, and scalable

That is the shift from typist to director.

The New $10,000 Skill: Knowing Where to Tap

In the old joke, the expert got paid not for swinging the hammer but for knowing precisely where to swing it.

In software today, "knowing where to tap" looks like:

- Knowing which components should exist in a system

- Understanding where state should live and how data should flow

- Picking appropriate patterns, boundaries, and interfaces

- Anticipating failure modes, edge cases, and performance issues

AI can happily generate code that compiles, but it cannot (yet) reliably guarantee that the architecture behind that code is:

- Maintainable by a team over years

- Resilient under real-world load and failure

- Safe from common security pitfalls

- Adaptable when requirements inevitably change

That responsibility still sits with human engineers who understand systems at a deeper level.

Adam Janes underlines this with two crucial observations:

"You can't effectively direct an AI if you don't understand system architecture."

"You can't spot a hallucination if you don't know what the code is supposed to do."

AI can confidently produce nonsense that looks plausible. Without strong mental models of how software should behave, you might never notice.

Why System Architecture Matters More Than Ever

Before AI coding tools, weak architecture and mediocre design were often masked by the sheer effort required to write code. A messy system might have been tolerated because rewriting it was expensive.

Now, AI lowers the cost of writing bad code just as much as it lowers the cost of writing good code.

If you ask an AI to "build a user authentication system" without specifying:

- How it should handle password resets

- How to store and hash credentials

- How to manage sessions and tokens

- How to log and audit access

...you might get something that appears to work in a demo but is dangerously insecure in production.

Good architecture is the difference between:

- A codebase that crumbles under growth, and

- A system that scales with your product and team

AI is a multiplier. It multiplies good decisions into great outcomes — and bad decisions into disasters that arrive faster than ever.

The Real Question: Can You Direct the AI?

Adam Janes reframes the conversation around AI and coding with a powerful shift in perspective. He writes that the question is no longer:

"Can AI write this code?"

That question is already answered. Yes, in many cases, it can.

The more important question is:

"Do you know enough to tell it what to write?"

This is a deeper, more uncomfortable question because it puts the spotlight back on human expertise. It asks whether:

- You can break a vague problem into clear, testable steps

- You understand the trade-offs among different designs

- You can recognize when an AI-generated solution is subtly wrong

Directing AI requires a mix of:

- Domain understanding: What is the business problem? What are real user needs?

- Technical judgment: Which approach will be reliable, secure, and maintainable?

- Critical thinking: Does this result actually make sense?

Without those, you end up accepting whatever the AI gives you — and that is a risky way to build systems.

Preparing for the Future Adam Janes Describes

So, how do you prepare for the future that Adam Janes is pointing to — a future where the hammer swing is cheap, but the knowledge is priceless?

Here are a few concrete directions:

1. Deepen Your System Architecture Skills

Study how real-world systems are designed:

- Read architecture case studies from major tech companies

- Learn common patterns: CQRS, event-driven systems, microservices vs. monoliths

- Practice drawing diagrams before writing code

The goal is to train yourself to think in terms of flows, boundaries, and responsibilities, not just in terms of functions and classes.

2. Practice Explaining Problems Clearly

If you want to direct AI effectively, you need to become excellent at describing:

- The inputs and outputs you expect

- The constraints you care about (performance, cost, security, UX)

- The edge cases you know must be handled

This is good engineering practice even without AI, but with AI it becomes essential. A vague prompt yields a vague system.

3. Learn to Audit AI-Generated Code

Treat AI as a powerful but junior collaborator. That means:

- Reading every line of generated code in critical systems

- Asking, "What could go wrong here?" and "What assumptions is this making?"

- Writing tests that validate not just happy paths, but failure scenarios

The better you become at quickly evaluating designs and implementations, the more leverage AI tools will give you.

4. Build a Portfolio of Directed Work

One of the best ways to prove you "know where to tap" is to show projects where:

- You defined the architecture and key decisions

- You used AI tools to accelerate implementation

- You can explain why things are structured the way they are

Employers and clients will increasingly look for people who can own outcomes, not just write code.

The Takeaway: Become the Expert with the Hammer

Adam Janes's post feels viral not just because it is clever, but because it captures an anxiety and an opportunity at the same time.

Yes, AI is changing software development. Yes, it can already do much of the "tapping" for us. But the rare, expensive, irreplaceable skill is still the same as in the old joke: knowing where to tap.

If you focus on:

- Understanding systems deeply

- Making sound architectural decisions

- Directing AI instead of competing with it

...you position yourself as the expert with the hammer — the person whose judgment is worth $10,000 even if the swing itself costs almost nothing.

As Adam Janes implicitly asks at the end of his post: Are you preparing for that future?

This blog post expands on a viral LinkedIn post by Adam Janes. View the original LinkedIn post →